“If a man ain’t never been hurt, he won’t understand it — but the rest of ’em will.”

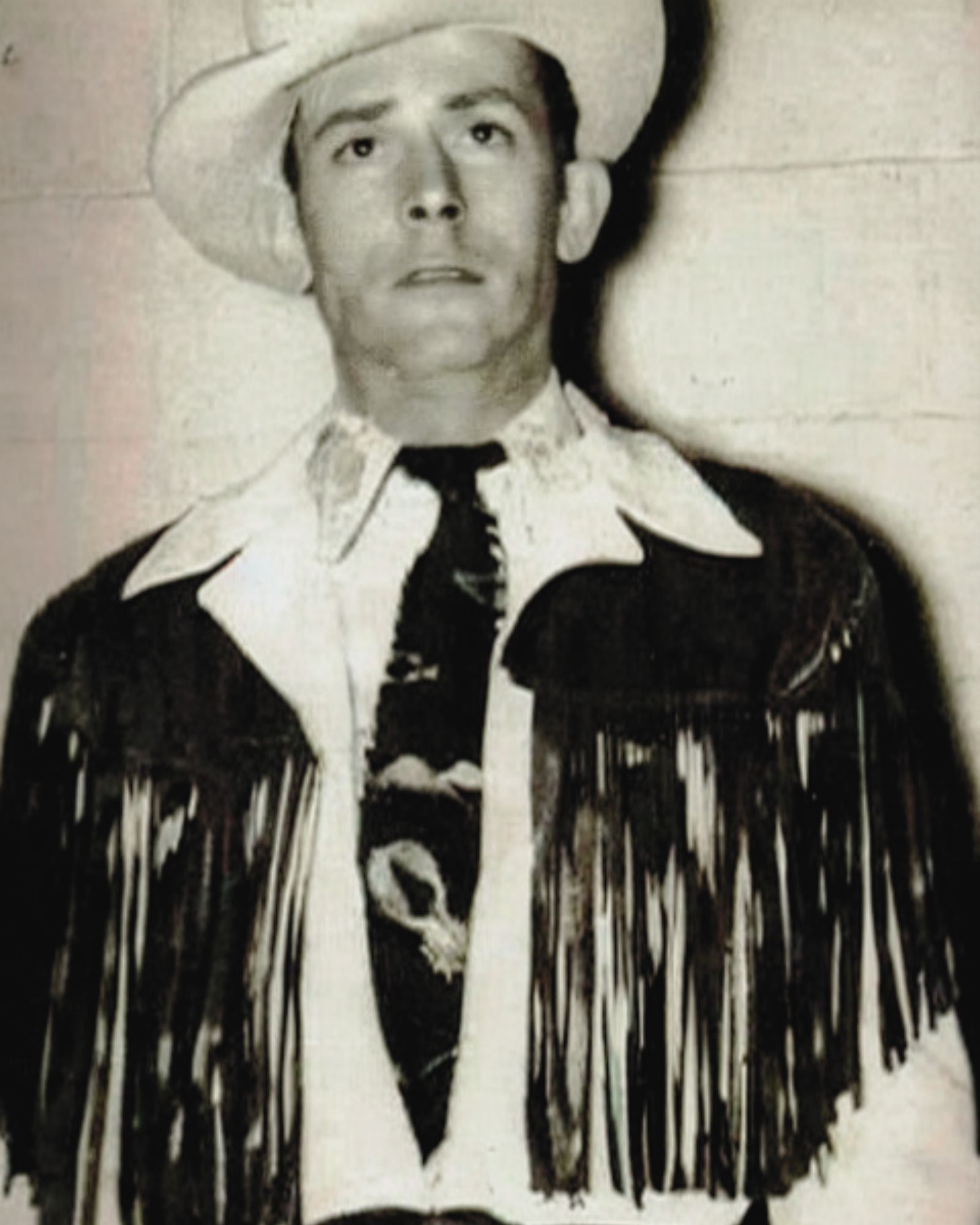

It was more than a quote — it was Hank Williams’s truth, carved out of heartbreak and sleepless nights. That winter evening in 1950 felt colder than usual, not just because of the season, but because something in Hank had frozen over. The pain in his back was nothing compared to the ache in his heart. Audrey had come and gone like a passing storm, leaving the scent of perfume and regret behind. The door’s quiet click after she left sounded like an ending — and perhaps, a beginning too.

Hank stared at the ceiling, the sterile hospital light flickering above him, and whispered those words that would soon echo through jukeboxes and dance halls across America: “She’s got a cold, cold heart.” He didn’t plan to write a song that night. He planned to survive it. But as he reached for his guitar — his only constant companion — something raw and divine moved through him. The chords stumbled out like tears, uneven but true.

By dawn, “Cold, Cold Heart” wasn’t just a song. It was a wound turned into poetry. When he played it for Fred Rose, the room went quiet. “Too sad,” they said. But Hank knew better. Sadness was the language of the people he sang for — the lonely, the bruised, the ones still waiting by the phone for someone who’d stopped calling.

When the record hit the airwaves, the world didn’t just listen — it felt. Listeners saw themselves in that trembling voice, that confession of a man who had loved too deeply and lost too much. Tony Bennett would later turn it into a pop hit, but no one could touch the way Hank sang it — that cracked edge in his voice, like a man smiling through a wound that would never heal.

Every time he performed it, under the stage lights and cigarette haze, it wasn’t fame he was chasing. It was peace. And somewhere between the fiddle and the silence, he found a piece of it.

“Cold, Cold Heart” wasn’t just a country song — it was the sound of a man telling the world what it means to love someone who’s already gone. And in that truth, Hank Williams turned his pain into something eternal.